Bloody tortures of the Middle Age Part 1

In the treatise of the witch hunter Pierre de Lancre “the picture of the impermanence of evil angels and demons,” published in 1612, describes the atrocities perpetrated by the servants of the devil. Accompany the text very illustration of the Polish engraver Jan Sarnco. A reader faces the coven, where they eat a bread made from black flour, go on the ground, strewn with the bones of unbaptized babies, flesh of the hanged, and “other creepy rotting corpses.” De Lancer relishes the details of the ritual of the evil forces, and Sarnco in detail brings them into the visual image: a monstrous bunch in the middle of rotting flesh. Words and images produce on the reader an indelible impression. In an article published in the journal Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Australian historian Lyndall Roper tells how “scientific” treatises on witches and demons turned into entertaining literary genre.

“The picture of impermanence…” — more a literary work than a scientific, because demonology was considered a science of evil, an offshoot of theology, philosophy and metaphysics. Modern researchers the witch hunters are usually classified as similar treatises to the genre of medieval fiction. It is hard to imagine that books, which have killed many people recognised witches and wizards, can dapple and humor intended in particular for leisure reading, but it is.

The sleep of reason

The close relationship between demonology and literature can be traced in the treatise of the philosopher Jean Boden De la demonomanie des sorciers, is dedicated to the witchcraft. This work is intended not so much for “experts” as to the General public. The author explores own diseased mind. Talks about the dreams of his friend (that friend, most likely, he was Boden), which appear white and red horses, and in good spirits, handing out tips on how to act in everyday life.

In addition, the book describes the art of fly tying, therefore, to induce impotence — this Boden was told a certain noble lady, whose name he tactfully does not name. The author writes about witches of Africa and lycanthropy in Europe, about how during the journey, he and all the inhabitants of the house where he stopped, cursed by a beggar, appeared dressed as a witch.

The whole book is riddled with such stories, it is not just an intellectual treatise, it is full of evidence about the experiences, dreams, and emotional dilemmas of the Boden. Here and there in the text there are strange stories and fables.

A medieval Thriller

Treatise Boden is based on the famous demonic work of Inquisitor Heinrich Kramer the Hammer of witches in 1486. Ostensibly academic, the text is replete with logical inconsistencies and, again, the stories are anecdotal in nature, over which, it seems, chuckles the author. His style and content was taking advantage of other writers of the time. Undoubtedly, the style of works varies, but the common features are obvious — largely because each of the authors parasitize on the ideas of predecessors.

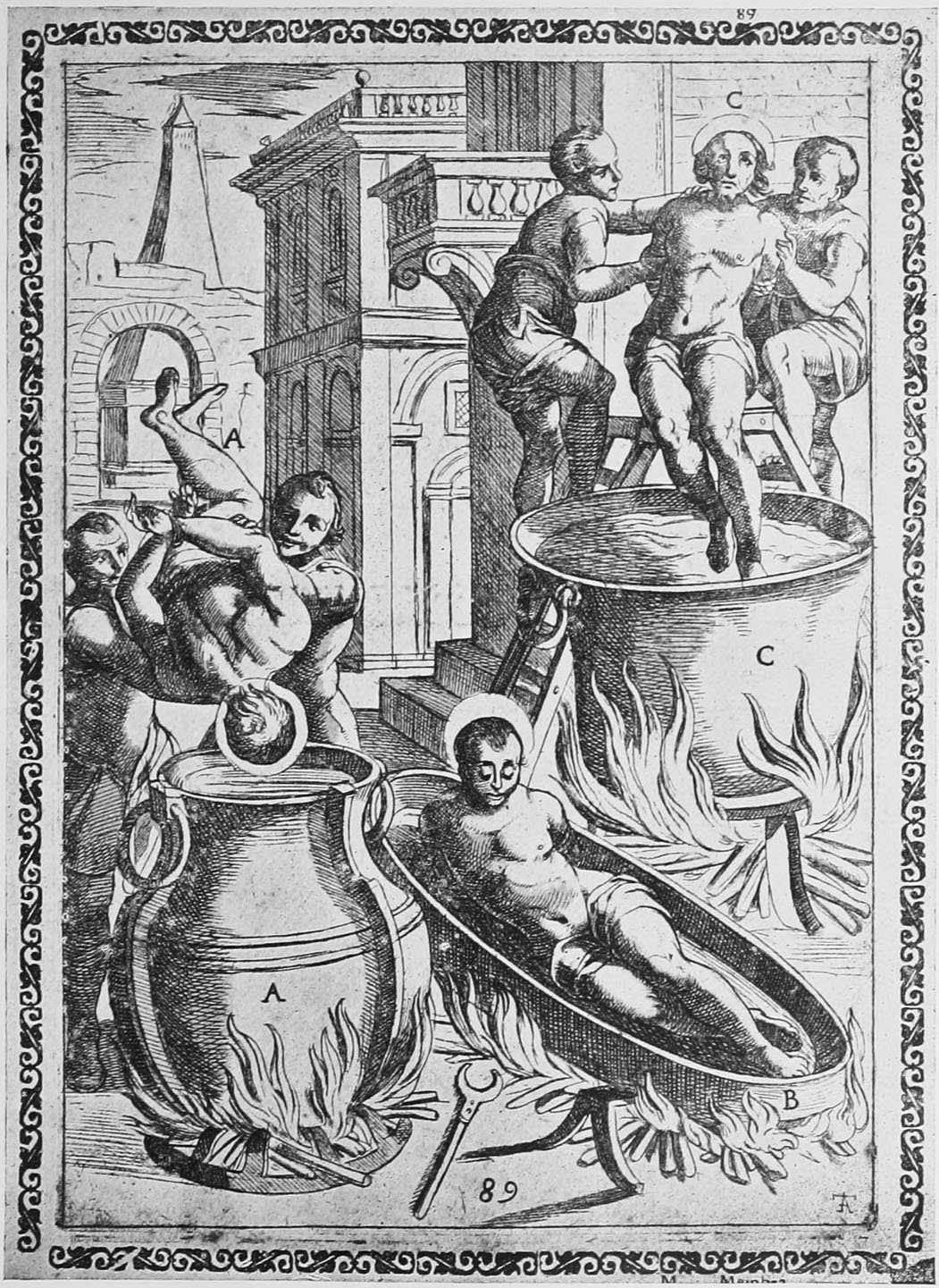

Illustration by Jan Sarnco to the treatise of Pierre de Lancre “the picture of the impermanence of evil angels and demons”

Illustration by Jan Sarnco to the treatise of Pierre de Lancre “the picture of the impermanence of evil angels and demons”

Illustration for the article “Witchcraft and the western imagination”

As illustrations accompanying the text, these treatises abound in descriptions of bloody rituals. In “Hammer of witches” tells of the birth grandmother, who murdered more than forty babies, sticking needles in their skulls at birth.

Witch hunter Nicolas Remy wrote about two witches dug from the grave the bodies of two children. One of them allegedly tore off his right arm, then the limb “burning blue sulfur flame,” lighting up the countryside. When they were finished their job, the hand was intact, “though it was not a tinder for the fire.” Remy mentions about babies who are ripped from his mother’s womb and roasted alive, by concluding this passage with the phrase: “But, perhaps, enough to say on this particularly unpleasant subject.” Definitely, all of this was to shock and appall the reader, and savoring Gory details similar to similar techniques used in modern horror films.

Witch as the character gained a life of its own. As the proud owners of cheap prints, painting, turned them into works of art, and the authors of treatises on demonology XVI-XVII centuries decorated their works of fictional dialogue and colorful descriptions of the covens and other disgusting rituals. Resorting to extravagant hyperbole, they were working fine literature.

In the scene coven de Lancer has been particularly active in demonstrating their writing skills. With undisguised pleasure, detail, he talks about the half naked bodies rushing to the meeting place on broomsticks from different angles, and structures the text in such a way as to create in the mind of the reader an amazing panoramic view of the unfolding events. Similarly, the act and other demonologists. Such descriptions capture the imagination and easy to remember.

In addition to the exploitation of terror and superstition, demonology often turned to humor, based on the medieval tradition of ridiculing the devil. In “Hammer of witches” there is a passage about witches stealing penises to keep them as Pets in the nest. Mentioned there’s a priest, deprived of his manhood, is a stone in the garden of the clergy of low rank. Over them willingly laughed the monks of the Dominican order, to which belonged the author of the treatise of Heinrich Kramer.